The Oars of 64

Special thanks to classmate Topher Cutler for assembling this delightful and heartfelt history, far from over, of the rowers of the Class of 1964 as they traversed from Nobles to Harvard College and beyond.

[written and compiled by Topher Cutler with enthusiastic participation and wonderful stories from Sandy Bolster, Alan Gauld, Dick Grossman, Ned Lawson and B Wolbach]

In the fall of 1964, five of the eighteen Nobles classmates attending Harvard walked into the

Newell Boat House to try out for the Lightweight and Heavyweight crews. Four were

experienced crew mates. One had traded in his thirty-four inch, hickory, baseball bat for a

twelve foot, spruce, sweep oar. A sixth classmate joined them late that fall after a stint on the

freshman soccer team. These six classmates would spend the next four years in one of the most

competitive rowing programs in the country, as heavyweight rowers, lightweight rowers and a

coxswain.

Harvard’s heavyweight program had produced a nationally recognized eight-oared crew in 1963

and a 1964 crew had that competed in that year’s Olympic trials, coming second to the Vesper

Crew that won the gold medal in Tokyo. Five members of that ’64 crew did compete in the

Tokyo Olympics as the U.S. entry for coxed fours. The atmosphere in the boathouse in that fall

of ’64 was heady and full of subliminal striving toward the ’68 Olympics in Mexico City. In the

ensuing three years, the striving became palpable as the Varsity Heavyweights extended an

unbroken string of winning races, including a Pan American gold medal and a Silver Medal at

the ’67 World Championships. Meanwhile, the Lightweight Varsity posted two undefeated

seasons and captured the Thames Cup at the Royal Henley Regatta in 1966 and returned to

European regattas in 1968. The six classmates coxed and rowed through the thick of

competition across the three boats (Varsity, Junior Varsity and 3d Varsity) on each of the

Heavyweight and Lightweight squads.

Rowing is a unique, if not odd (sitting down and going backwards) athletic endeavor. Rowers

train in and race several types of boats with different numbers of seats pulling on either small

sculls or longer sweep oars. There are the familiar single scull and four-oared and the eightoared

shells with coxswain. But there are also double sculls, quadruple sculls, pair-oared shells

with and without coxswain and four–oared shells without coxswain.

Rowing’s uniqueness lies in sameness: every rower does exactly the same thing with exactly the

same equipment, mile after mile, hour after hour at about 34 strokes per minute. There is no

evident, spectacular skill: no rink-long rush to score the overtime goal; no flurry of three

pointers; no striking out the side in the ninth inning or crushing the go ahead home run; no

threading the secondary on a dazzling touchdown run or intercepting a pass on your goal line.

Rowing is insanely repetitive, intensely focused and, for long stretches exceedingly

monotonous.

It is hard work in pursuit of, if only for a few strokes or a few minutes, the

sublime, simultaneous sensations of unity and singularity that create an incomparable,

seemingly effortless flight across water. It is the ultimate team sport.

In the midst of this grueling, windmill-tilting work, sits the coxswain: a calm steersman, a racing

tactician, and a discerning coach. The coaching is paramount. The coxswain constantly coaches

for better technique, timing, and blade-work. His ability to motivate his oarsmen beyond the

mental limits of their physical exertion can make the difference in tight races. Capable

coxswains help rowers become capable crews. Great coxswains help capable crews become

great crews.

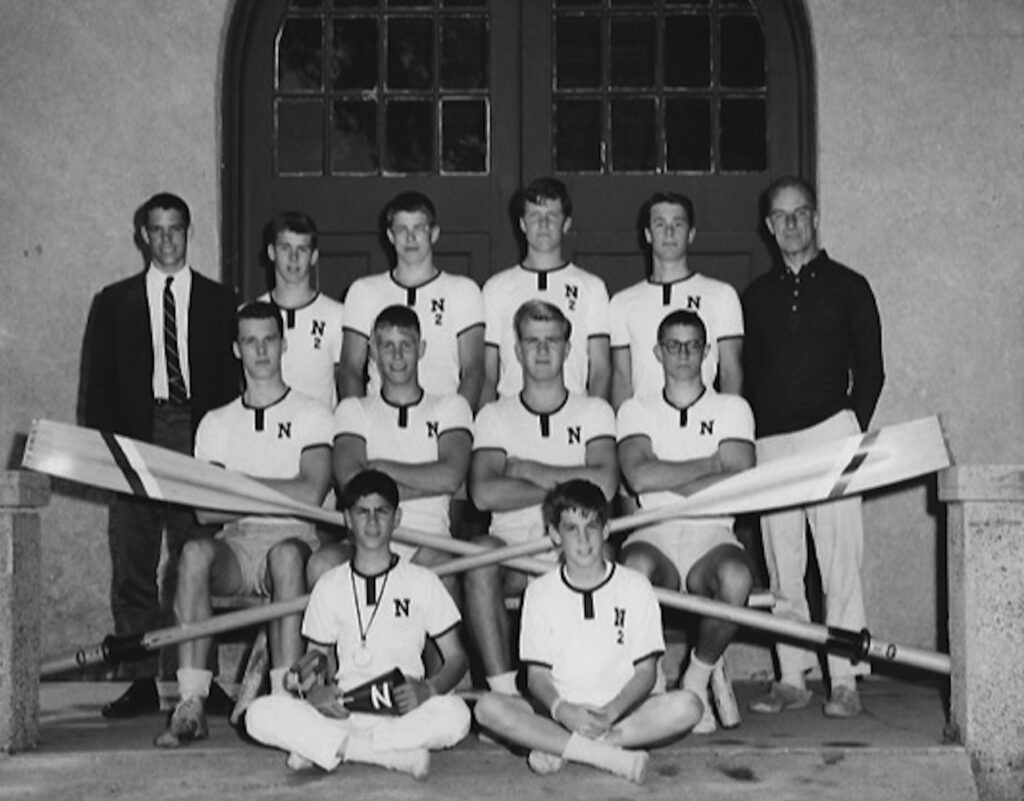

The Nobles Years

In the Nobles years of 1960-61, classmates Sandy Bolster, Alan Gauld, Ned Lawson and Topher

Cutler began their rowing odysseys at the Saltonstall Boathouse on Motley’s Pond under

coaches Ben Lawson and Bob Warner. Topher had coxed the upper class racing boats for two

years in his 6th and 5th classes. Dick Grossman arrived in the 4th class, and, quickly proving his

worth, wound up coxing the 1st Boat for three years. The four rowing classmates learned

together in various combinations on the training boats. Then, as upper classmen, moved onto

and up through the four racing boats. Lawson, Gauld and Cutler raced sophomore year on the

3d Boat with Sandy Darrell. Junior year Bolster joined them on the 2nd Boat, as Gauld jumped to

the 1st Boat to race with classmates Grossman and David Brooks.

In the spring of ’64 with a quarter of the senior class (including Darrell, Brooks, Watson,

Glidden, Burr, Reece) on the racing boats, Coach Warner’s crews turned in the best season in

many years. Reece, Burr and Watson powered the 3d boat. The Bolster-Gauld combination

(harbinger of greatness) with Glidden raced on the 2nd boat, stroked by David Brooks’ brother

Steve, a future Mexico City Olympian with the Harvard crew. Grossman, for the third year,

coxed the 1st boat with Cutler, Lawson and Sandy Darrell joining David Brooks. The Lawson-

Cutler pairing lasted all four Nobles years.

Topher recalls:

“At 145 pounds, I was forever grateful for Bull’s heavyweight strength,

especially in the headwinds. And when joined by two more powerhouses,

Brooksie and Darrelli, what more could a lightweight stroke ask for?”

The early ‘60s were the last years of a training regime that had existed since the early 1900s.

Coach Warner emphasized technique and longevity together in a boat. There was not much

swapping of rowers among the boats once racing season started. And so, the five classmates

arrived at Newell in the fall of ’64 with four springs of training miles and decent technique, but

were soon to experience a completely revamped, revolutionary, nine-month training regimen.

It included weight lifting, interval work, indoor tank rowing, stadium running (40 reps of 38

steps bottom to top in under 10 seconds), and the cursed arrival of a cast iron flywheel,

precursor to the now ubiquitous ergometer, by which an oarsman’s output could be measured,

graphed and compared to that of boat mates. This multiphasic training over the entire

academic year was intense preparation for the on-water seat-racing (swapping individual

oarsmen between two boats in racing workouts) in the spring. Eventually, the oarsmen and

coxswains received assignments to one of three racing boats, Varsity, Junior Varsity or 3V.

All this training prepped the crews for about thirty-seven minutes of actual racing in five,

weekend regattas per season. Of course, the Heavyweights enjoyed the extra allure and legacy

of America’s oldest intercollegiate competition, the multi-mile races with Yale on the Thames

River at New London, Connecticut.

Into this radically transforming regimen stepped the sixth classmate, B. Wolbach, who had been

bedazzled by the recruitment pitch of the Harvard ’64 Olympians scouting the Freshmen for

tall, strong candidates.

As B said later:

“I was a sucker for the really big guys in Olympic blazers who were talking up

the ’68 Olympics.”

He started from scratch, but like many recruits who had not rowed in school, did not have to

‘unlearn’ prior technique. B was a quick learner, attracted to a sport that simply asked him, and

everyone, for total commitment.

1965, Freshmen Year at Harvard’s Newell Boat House

Five classmates all made the freshman racing boats in the spring of ’65. Bolster and Gauld

anchored an undefeated Lightweight boat (average oarsman weight: 150 lbs.) with Cutler

joining them for two races. Lawson captained (once a captain always a captain) an undefeated

Heavyweight boat, while Wolbach rowed on a very competitive, second Heavyweight boat.

Grossman opted for a concentrated study semester.

1966 Sophomore Year

The jump sophomore year to the Varsity squads was a spectacular one for Bolster and Gauld.

They became a stalwart combination in the #6 and #5 seats on the Varsity Lightweight crew

that went undefeated that year. Alan was, pound for pound, one of the strongest oars at

Nobles and Harvard. Dick Grossman, who coxed Alan on the Nobles first boat in ’63 and as a

heavyweight at Newell junior year, opined:

“his connection with the water and great efficiency made him more effective

than larger heavyweights”.

There was no doubt that Alan was “a real boat-mover”, the one guy who through his intensity

could practically ‘will’ a boat over the line first. One of his boat mates fondly called him “the

Beast”. Alan was also extending his family’s lightweight history, following his father, Gordon,

H’27 and his Nobles brother Stewart, H’65, N’61, who had both rowed with the Lightweights.

Sandy brought his inimitable style of silky power to every crew on which he rowed. His

presence in a boat quieted down all the extraneous movement of bodies, heads and hands. His

timing with the stroke oar never varied, always enhancing the boat’s rhythm and swing.

Topher claimed:

“Sandy and I rowed together for eight years through countless miles on

the Charles River. He was the smoothest oar with whom I ever rowed.

He simply never upset a boat, but made it faster by not doing so with his fluid style.”

With Bolster and Gauld, this exceptional ’66 crew (stroked by Monk Terry, a future two time

Olympian and Silver Medal winner), travelled overseas and rowed five winning races in four

days at England’s Royal Henley Regatta in July to win the Thames Cup, right in front of the

Queen, no less!

Meanwhile, on the Heavyweights, Lawson and Wolbach made the JV Boat that went

undefeated until being upset by Yale in the three-mile race at New London. Dick Grossman

coxed his two classmates for that race and recalls it being profoundly disappointing. Wolbach

remembers only nearly blacking out over the last quarter mile. Grossman, having coxed and

coached his Nobles Captain on both the upper and lower Charles, characterized his rowing this

way.

“Ned was ‘Bull’. He was very strong and pulled very hard, very consistently.

Nothing stopped him – waves, wind, uncomfortable situations.

He was one hundred per cent dependable.”

That summer of ’66, a small group of Harvard Heavyweights rowed out of Union Boat Club (at

the foot of Beacon Hill on the Charles River Basin) with the goal of qualifying for the US National

Team, which would compete at the ’66 World Championships in Bled, Yugoslavia. Grossman

and Wolbach qualified for the team in the coxed four trials race in Philadelphia by sprinting past

the stern four of the Vesper eight that had defeated Harvard at Henley in 1965 and again at the

Olympic Trials in 1964.

As happens regularly in rowing, B lost his seat to another oarsman just before the trip, but

stayed on the team as a ‘spare’. The ‘other’ oarsman turned out be Larry Hough, who was

quickly earning his reputation as the finest sweep oar in the country, and who went on to

national championships, world titles and the Olympics over the next several years. Very rare air

indeed for the former Nobles baseball catcher of whom Grossman said:

“B was a catcher, a coachable catcher. He had no baggage. He was willing

to learn something new with no preconceptions of how it should be done,

and consequently learned to row well through an intensive college course…..

and kept learning. During my sophomore summer, the two oarsmen I had

the most respect for were B and Andy Larkin (future ’67 Worlds Silver Medal

and ’68 Olympian) both of whom had been in the 2nd freshman boat

only a year earlier and had developed into National Team oarsmen.“

Later that fall at the second Head of the Charles Regatta, Lawson and Wolbach won the first

place medal in the coxed four race, with the aforementioned Andy Larkin at stroke. Dick was

already refining his abilities at spotting talent and commitment.

1967 Junior Year

In the spring of ‘67 Gauld, having outgrown the weight limitation of 160 lbs. on the

Lightweights, rowed with Grossman on the 3d Heavyweight boat, while Lawson and Wolbach,

who had made the Varsity boat for a couple of early races, raced on the JV boat. The 3d and JV

boats were switched for the Yale races, allowing Gauld to row to victory in the three-mile race,

while Grossman, who had been briefly promoted to the JV boat, ended up coxing B and Ned

through a miserable loss in the two-mile race. The subjective decisions of coaches about which

oarsmen or entire crews produce the fastest results can be brutal for the oarsmen, brilliant or

disastrous for the racing, and simultaneously second-guessed by everyone.

Meanwhile, Cutler had moved up to the Varsity Lights, who had a winning season but lost the

Eastern Sprint title to Cornell. Post season, he rowed in a winning straight four (no coxswain) at

the American Henley Regatta in Worcester. Bolster rowed on the JV boat and anchored yet

another undefeated crew and Eastern Sprints winner.

1968 Senior Year

In the senior spring of ’68, Cutler remained on the Varsity Lights, who went undefeated and

won the Eastern Sprints and were invited to train with the Heavyweights for their Yale races at

Red Top, the seasonal training camp in Ledyard, Connecticut. The Lights were prepping for a

trip to Amsterdam for races against Eastern European crews training for the Olympics, and then

on to Henley, England to recapture the Thames Cup. The Heavyweight coach, Harry Parker, had

wanted to make his Varsity crew faster off the start for the upcoming Olympic Trials. The

Varsity Lights were quicker for the first 500 meters, so they became the ‘rabbit’ for the Heavies

to chase. On a family note, as a member of the first Lightweight crew invited to Red Top,

Topher realized a personal goal to row where four Cutlers of two earlier Volkman and Nobles

generations had trained and raced against Yale.

Red Top was terrific training for the Lights in their Amsterdam races, which all went very well

for the first 750 meters of the standard 2000 meter course, but turned sobering and painful for

the last 1250 meters. The Lightweights were quick and fast, but once the Heavyweights’ big,

‘slow twitch’ muscles kicked in, they were no match for the 200+ pound Olympic-bound

oarsmen.

At Henley the racing turned awful. The Royal Regatta suffered through a flooded Thames River

that spring, which created disastrous, one-lane results for the racing, including an early loss in

The Thames Cup for the Harvard Lights. Cutler, moreover, had the dubious distinction of

extending the family losing streak at Henley. His grandfather, Roger, H’11, Volkman ‘07, lost in

The Grand Challenge Cup of 1914; his father, Robert, H’35, N’31, lost in the Diamond Sculls of

1933; and an uncle, George, H’40, lost in the Thames Cup in 1938, racing with the Harvard

Lights. There’s a message in there somewhere about his family’s ‘recessive’, rowing gene.

The JV Lightweights, with Bolster aboard in his customary #6 seat, were unstoppable, went

undefeated and won the Eastern Sprints again. With that final race, Sandy set a unique record.

Each college crew he rowed on went undefeated and won the Eastern Sprints every year of his

four college years. Counting the Henley Regatta, his racing record was an astounding 29-0!

Whether Freshman, JV or Varsity, Sandy made every one of his boats a winner with his quiet

power and superb style.

On the Heavyweights, Grossman coxed the JV boat with future, two-time Olympian Monk Terry

at stroke, while Lawson and Gauld trained in and raced a coxed four, notably on the Severn

River at Annapolis against Navy. On the way home, according to Ned, Alan disappeared into

New York City for a few days of ‘R&R’.

Rowing After College

After college, the six classmates followed predictably different paths: military service, grad

schools, travel, entry-level jobs and marriages took precedent. A few stayed close to rowing and

one of them embraced it as a lifelong passion and career. Dick Grossman, while completing

Army Reserve Service and law school, maintained his position on the US National Rowing Team

for several years, first as a competitor in international regattas and later as a team manager.

Dick was first selected as Alternate Coxswain for the 1968 U.S. Olympic Team, an assignment he

had to forgo because of his military duties. In 1973 and 1975 he won bronze and silver medals

coxing the U.S. Lightweight 8 at the European Championships (Moscow) and World

Championships (Nottingham, GB) respectively. Of note, his stroke for the Europeans was Rick

Grogan, N’71, who Dick reported rowed nearly unconscious in the last 500 meters of the race.

In 1985 he won an international gold medal on a coxed four at the Masters World

Championships in Toronto, stroked by none other than ’68 Olympian Steve Brooks, H’70, N’66.

His service on U.S. National Teams continued as the Lightweights Head Manager for the World

Championships of 1981 (Munich), 1982 (Lucerne) and 1984 (Montreal).

Back on U.S. shores, Dick started his thirty year coaching tenure at Dartmouth in 1975, after a

particularly special rowing race involving one of his five classmates….. Gauld. Dick wrote about

that race and his ‘aha’ moment in our 50th Reunion Report.

On the 18th of April in ’75, on the 200th anniversary of Paul Revere’s ride,

(I was a lawyer at the time) a rowing team originating in Cambridge, England

challenged a similar team in Cambridge, Massachusetts to a crew race for the glory

of the Empire/Colonies (depends on your side – Gauld rowed for the British,

something about his Scottish ancestry. I coxed for the U.S.A.

It didn’t matter who won (we did – again; and the Pimms was good),

but the event brought me to the realization that the practice of law was keeping me

from my real passion – rowing. I resigned the next day, raced for the U.S.A.

that summer and moved to New Hampshire in October to become a crew coach.”

And so began Dick’s 30 years of coaching crew at Dartmouth College, twenty-seven of them

with the Varsity Lightweights. His best crews won the Eastern Sprints in ’93 and ’94, set course

records and raced at Henley. He also ran a summer program that entered crews in the U.S.

national championships and the Canadian Henley at St. Catherine’s, and they won their fair

share of medals.

Off the water, but never very far off it, Dick helped found the Upper Valley Rowing Foundation

to bring rowers who were not affiliated with the college onto the river. He served as an

occasional coach and board member for many years. To further the spread of rowing

throughout New England, and to supplement his coaching salary, he started a shell-leasing

business in 1990, North Country Racing Shells, sending boats to any crew in need of a boat for

regattas or training camps in the south. Through these years he handed down enough

coxswain’s knowledge that when son TJ (Theodore Jared) coxed a four-oared crew from the

University of California at the IRA Championships, he won, beating thirty-two other boats. His

father could barely heft the bag full of the losers’ shirts. (Losing crews ‘hand over’ their racing

shirts to the victor.)

For the past fifty plus years Dick coxed crews in every Head of the Charles Regatta from 1965 to

2020. His success on superb crews (remember the assertion about great coxswains) was

extraordinary. His first win was in 1967 in a coxed 4 with the Harvard Heavies. Then followed

wins in the Championship 8s in 1970 and ’71, in the Lightweight, coxed 4s in 1973 and ’75, and

the Masters coxed 4s and Club 4s in the 1980s. And, from 2006 to 2020 coxing the same

Masters 8, his crew won the race eight times, including a streak of six in a row! In addition to

becoming a major contributor to American rowing, our modest Nobles classmate, whether

racing on European or North American waters, was a world-class competitor.

When reflecting back on all his experiences and contributions to the sport, Dick said:

“I got into rowing for the competition and for the satisfaction achieved by making

a boat go fast with the rowers swinging together. Those are still the aspects of the

sport I enjoy the most on the water, but the efforts expended in making those things

happen teach us lessons valuable in both rowing and life.”

B. Wolbach turned to running marathons and ocean rowing after college. He rowed long ‘open

water’, ocean races for many years in the Blackburn Challenge around Cape Ann (20+ miles),

which he won numerous times in an ocean-going double, and in the Isle of Shoals races (7.5

miles) off of Kittery, Maine. After a thirty-eight year absence, he returned to the Head of the

Charles in 2006 to race in a single, and that same year raced in a mixed double in the World

Master Regatta in Princeton where he won a silver medal.

Sandy Bolster says that he gave up rowing on sliding seats, but, nonetheless, often raced heavy

dories in the harbors of mid-coast Maine. He remains a confirmed waterman, with a decade of

organic farming on the side, as a schooner captain, a Caribbean ‘live aboard’ cruising to Cuba, a

boatyard rigger and available crewman. As he wrote in the 50th Report:

“I’ve gone back to water-based activity, operating a small day-sail charter and private

sailing instruction business.”

Alan Gauld continued to row intermittently into the 1980s. In his post grad year in Scotland at

the University of Aberdeen, he joined a pick-up crew and raced again at Henley, only to be

defeated by… a Harvard Lightweight crew. By the late ‘70s he was sculling on the Potomac

River in Washington, and a couple of years later dodging barges on the ‘Three Rivers’

(Allegheny, Monongahela, Ohio) of Pittsburgh, something Cutler also experienced on the Upper

Mississippi in Minnesota. With his move to San Francisco in the early ‘80s, Alan continued

sculling out of Sausalito and rowing in eights with the Marin Rowing Club. His most recent

water-borne adventure was a kayaking a four-day circumnavigation of Lake Tahoe in 2014.

After college, Ned Lawson went to law school and then began thirty years of environmental

lawyering. In 1997 his environmental antenna detected a problem festering on his hometown

harbor of Duxbury. Where Ned saw problem, he also saw opportunity, for school kids, for his

community and for his real love….sailing. His career went ‘hard full rudder’ onto a new course.

“My decision to change careers was an easy one”, he said. “My principal

motivation was my desire to protect the site of a defunct Duxbury boatyard

from a non-water dependent use such as a restaurant. In addition, my love

of sailing and Duxbury Bay made me want to increase public access to the bay.”

Ned’s schoolmaster gene quickly combined with his sailing gene to envision a sailing school that

would become the Duxbury Bay Maritime School. A couple of years on, two local rowers who

had rowed in the ’72 Munich Olympics, pitched the concept of putting school kids and

adventuresome adults on the bay in rowing shells. Dick Grossman provided some ‘experienced’

shells, while Ned provided the rowing knowledge. The surrounding communities sent kids by

the hundreds. Ned wanted:

“children and adults to have a chance to learn experientially about such

things as selfless dedication to teammates, the importance of conditioning,

and an appreciation of the natural environment of Duxbury Bay.”

With enrollment in the hundreds, four years ago the School constructed an entire rowing

center, complete with boat bays, an erg room and rowing tanks for winter training. Along the

way Ned’s three daughters rowed successfully at Nobles or college. Cassie won a schoolgirls’

sprints race on Quinsigamond. Jennie stroked the Colby Varsity to the Division 3 Title on Lake

Lanier in Georgia and Meg too rowed a year on the Colby Varsity.

Ned served as the founding Executive Director for ten years and is still amazed at his original

vision’s extraordinary growth and community impact. His legacy is providing marvelous

opportunities to the folks of the south shore communities who are curious about anything

maritime and want to get out onto the waters of Duxbury Bay.

“Junior sailing was the initial program,”, Ned said, “and was followed by

a wide range of other programs including rowing for adults, women, juniors,

veterans, urban youth and people with disabilities. DBMS is wildly successful,

and has evolved far beyond my initial dreams. I have never looked back.”

Cutler also stayed close to water and skinny shells. Since 1975 he has lived within a few miles of

Worcester’s famed rowing course on Lake Quinsigamond. With the proliferation of ‘Head’

regattas all over New England (and the country), there were plenty of annual opportunities to

race among increasingly older and slower friends. He bought a used, wooden single scull in

1977 and car-topped it to regattas on the upper and lower Connecticut, the Merrimack, and the

Seekonk Rivers for many years.

He remarked:

“It’s The Head of the Charles that remains the best ‘on water’ reunion midst

challenging racing. From 1966 to 2016 I rowed in half of them, in a single, a double

or a ‘quad’, and always with mates from my college crews. In the 1971 Head,

my father (a 1936 Olympian with three other Nobles alums) and I became the first

‘parent/child’ entry, an event that now attracts a hundred rowers across generations.”

In 2015, Topher recruited three lightweight mates from 1967 to race with him at the Head in

the quadruple sculls event (4 rowers; 2 sculling oars each). The quad is still racing every fall,

now with a mix of different oarsmen from his college years, and is still the most senior crew in

the regatta. The racing is fun…. and slower each year. The camaraderie is the prize, as sixty

years of friendships re-energize. It’s all about what Dick told his incoming freshman every year:

“[that] rowing would not only provide them with a great challenge and experience,

but the sharing of that experience would provide them with some of their

best friends in life. While our rowing programs don’t create those friendships,

they put rowers in a position to make them happen.”

Alan would certainly agree as he became a fast friend with his #7 man, Bruce Stevenson, from

their undefeated ’66 Henley crew. In college they shared a love of Corvette Stingrays (Bruce ‘64,

blue; Alan ’66, red) and later, in the mid 70s, salmon fishing in the swells off the Oregon Coast.

Topher is now a confirmed ‘fair weather’ oar, avoiding the dark, cold, early morning paddles.

He mused:

“These days, I row when the sun is warming, the winds light and the lake clear

of powerboats. Getting in and out of the boat are the riskiest moments as old knees

wobble. Who knew when I coxed a 3d boat race on Quinsigamond in 1959 that I’d still

be paddling its waters sixty-three years on.

The sensations of gliding out onto the water sheet and dredging up the muscle

memories, remain a welcome tonic for the body and the mind. Inevitably, I begin

again to seek the perfect setup, the well-timed strokes and the rhythmic ‘swing’ as

the boat takes flight across the water

And then, as all six of us know so well, there comes the irresistible urge to crank up

the effort on the way home and glide back into the dock, satisfied with delusions

of speed and grace floating gently on the memories of The Oars of ’64.”

Thanks Topher – this is not only a labor of love, but a great read. Keep on rowing – many many thanks.

I loved this memoir. It’s not only the spirit that keeps the reader interested, it’s the writing as well.

An example:

Rowing’s uniqueness lies in sameness: every rower does exactly the same thing with exactly the

same equipment, mile after mile, hour after hour at about 34 strokes per minute. There is no

evident, spectacular skill: no rink-long rush to score the overtime goal; no flurry of three

pointers; no striking out the side in the ninth inning or crushing the go ahead home run; no

threading the secondary on a dazzling touchdown run or intercepting a pass on your goal line.

Rowing is insanely repetitive, intensely focused and, for long stretches exceedingly

monotonous.